Jun 28, 2023

The Radiologist Gaze

I don’t know how many doctors are familiar with Jacques Lacan’s theory of the image screen. I certainly wasn’t, until 2020, when I was perishing from COVID-19 complications and had the rest of my life to read esoterica. I was a radiology resident on the pandemic front lines in New York when I fell ill. The novel coronavirus was mysterious and strange, disseminating blood clots throughout my previously healthy body. We didn’t know where my next clot would be, or if it would claim my life. It could be a big bloody glob occluding one of my main pulmonary arteries, straining my heart and choking it dead. Or perhaps a chunky one in a vessel in my brain, causing a debilitating stroke. That would be the least palatable of all. To make a radiology report, we had to dictate our words into a little microphone; software transcribed it to text for the report. I already couldn’t dictate my radiology reports as fast as the hospital wanted me to. The last thing I needed was slurred speech.

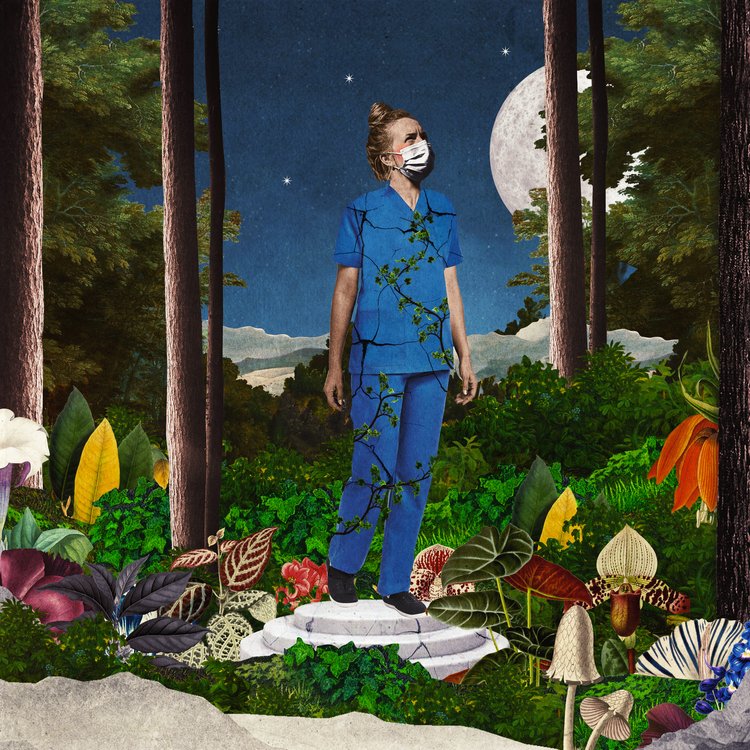

My doctor prescribed a bottle of petite red pills to thin my blood and prevent more clots. They were inscribed with “X”s, which seemed ominous. I took them nonetheless, twice a day- the first dose before donning my makeshift bandana mask and heading to work. And the second dose after witnessing a day’s worth of carnage unfold on the radiology screen.

It wasn’t long before the bleeding began. Blood drops would appear in unexpected places - dripping down the bathroom sink cabinet, trickling onto the floor after I emerged from the shower. Standard physician verbiage is to say that the patient “failed” anticoagulation. This is now considered gauche and insensitive, blaming patients for having side effects from medications we designed and prescribed. But whenever I tell my story, I say “I failed anticoagulation.” It’s the only phrasing that seems fitting - imbued with the shame that I can’t seem to shake, even 3 years later. Aspirin was my next poison.

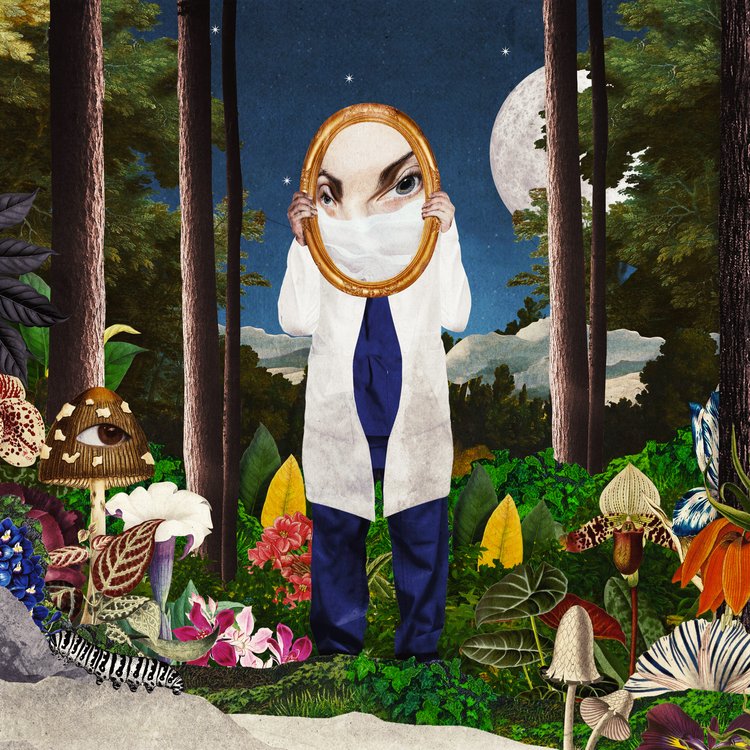

One of my pandemic purchases was an empty glass bottle from the 1910s with a peeling red Heroin Hydrochloride label. Over the next month, my aspirin, an acid, ate a hole in the cardboard disc underneath the bottle cap - something its previous contents couldn’t do in 100 years. My medication would soon eat a hole in my stomach, too. And with this ulcer, my troubles really began. I ignored the slow ooze of blood from my stomach ulcer for months. Each morsel of food became a scalpel blade in my stomach. At the end of each 12-hour shift, my eyes were too exhausted to notice my gaunt reflection. Soon, the medical images on the screen were my own. It was only then, seeing myself on the image screen, that I realized how far I had strayed from the light.

I worked on the pandemic front lines until I couldn’t anymore. Sometime during my convalescence in October 2020, I discovered the writings of Lacan. I pondered his concept of the image screen, which separates the viewer from the object. In doing so, the screen shields the viewer from the true essence of the object. This can sometimes be protective, in cases when the object is particularly revolting or heinous.

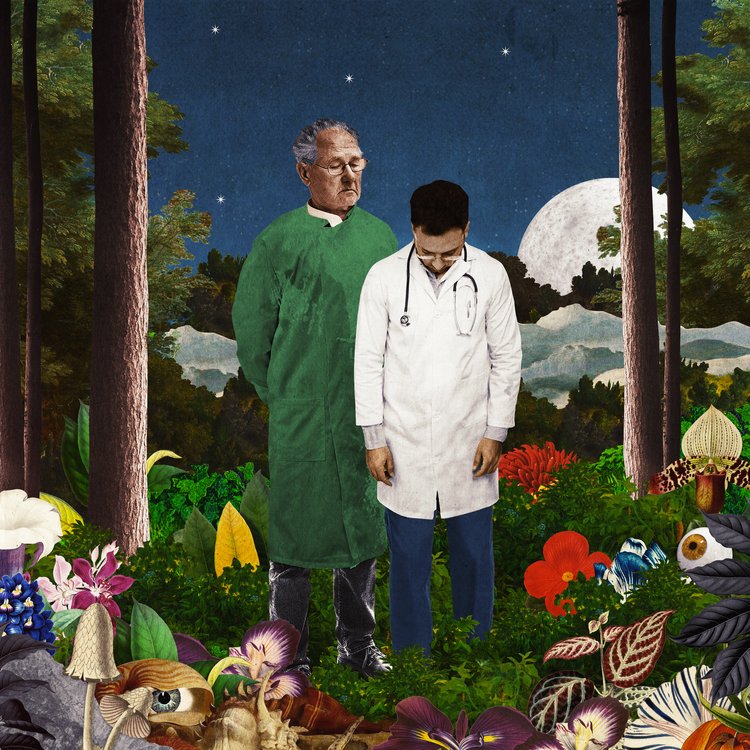

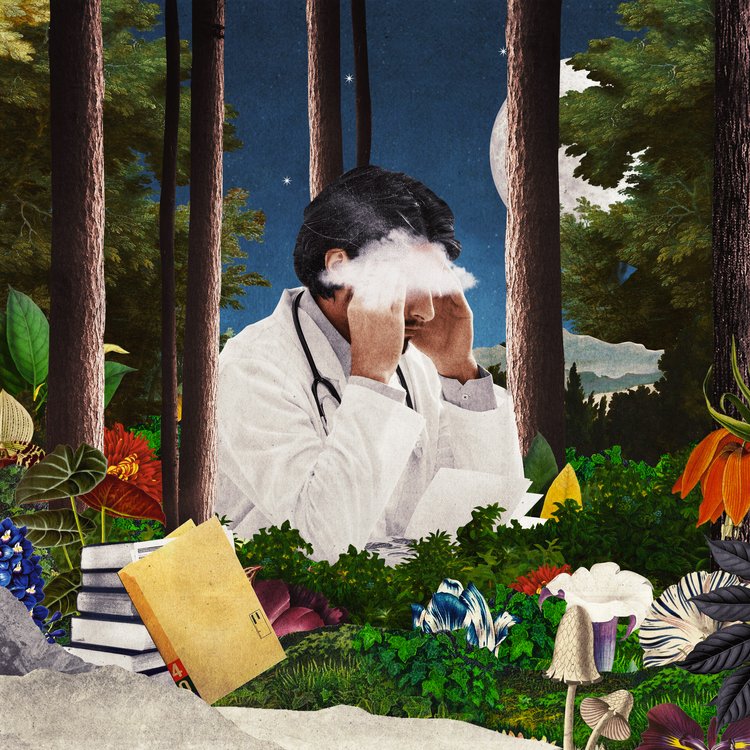

How many hours had I spent looking at patients through the image screen? Around 5,000, I calculated. The radiologist gaze is cold and technical, but voyeuristic nonetheless, stripping patients of their hospital gowns and skin to peer inside of their most intimate spaces. This screen allows us to hide in our dark reading rooms, unseen by the patient. Most radiologists love this - after all, they sought radiology over other specialties to leave the suffering, blood, and gore on the other side of the image screen.

The radiology image screen has two functions, I realized on my deathbed. 1) It transmutes patients into greyscale blobs, dehumanizing them, turning them into mere symbols to be interpreted. This transformation is made possible through the magic of physics and technology. We do not call them symbols, rather, we prefer the term signs. We apply these symbols to the images, which are themselves abstractions of the anatomy they represent. This second layer of abstraction is often lost to doctors. The grey blob on the screen is merely an arrangement of pixels; it never beat, fluttered, squeezed, or loved, yet we confidently proclaim it to be a person’s heart.

Radiologists don’t appreciate the beauty and horror in reducing a patient to a collection of symbols. I don’t think it’s because they aren’t familiar with the language of semiotics. Rather, it’s probably because they aren’t given the time or space to reflect on the lives that are being blasted into pixel smithereens, because the screen also 2) facilitates mass consumption of images. Depending on their specialty, patient-facing doctors see on the order of 20 ailing people each day, not masked by the image screen. Each one of those patients gets, on average, one imaging scan every day. So, radiologists read on the order of 100 imaging studies each shift. In these exams, the radiologist bears witness to dozens of internal catastrophes each hour. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag describes how observing so much human casualty and violence on the screen, whether on television or in photographs, dulls our perception of suffering. Our mass consumption of internal disasters on the radiology image screen normalizes them. The abstract nature of these emergencies further dehumanizes the patient - the white area of screen that should be black is actually a fatal torrent of blood pooling in the abdomen.

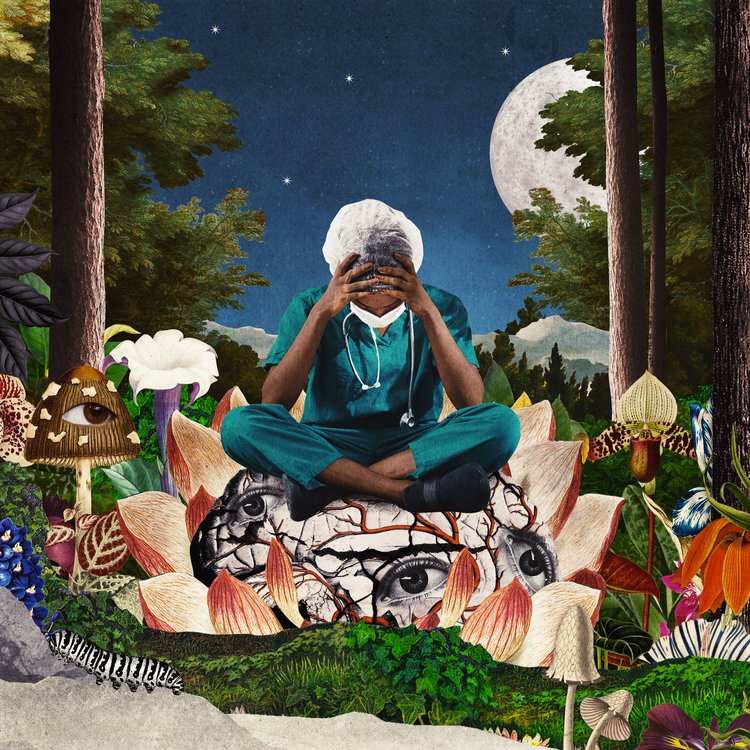

Despite the semiotics, the abstraction, and the loss of empathy that should have come with the mass consumption of images, my medical training made me seek humanity. I yearned to connect with these patients more, not less. Whenever I opened a scan, I spent too long reading about the patient in their medical chart, trying to piece together who they were as a person before they were mangled on the inside by disease. I saw deaths unfold on screen, off screen, and in the liminal spaces in between. Every so often, daily chest X-rays for a patient in the ICU would abruptly stop. When I was a happy, naïve junior resident, I thought a miracle had happened. It turns out they (almost) never do.

I wanted to mourn these patients, even the ones I never saw outside of the image screen. How haunting it was to peer inside of someone and witness how Death worked her magic. A bathroom stall became my makeshift altar to grieve. I could purge myself of urine and tears at the same time. When I returned to the reading room, my teachers never noticed my red eyes, or the tears that had yet to spill over my eyelids. I assumed they didn’t notice, but perhaps they didn’t care. I don’t know which one is worse. Was it possible to have visual PTSD in the context of seeing atrocities unfold on the radiology image screen? If so, I had it. And I wondered how many others did, too.

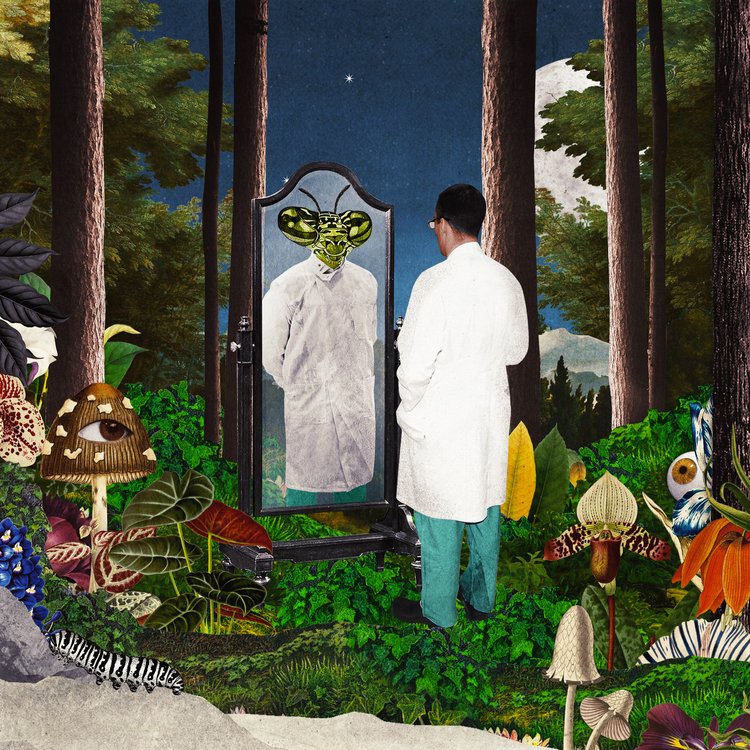

Sometime during my convalescence, The Met reopened its doors and became my haven to escape. I couldn’t help but gravitate towards the black and white photographs. There was one I spotted from across the small gallery. As I stood before the photograph, its aura squeezed the air out of my lungs. It was the image screen, blank and glowing white, as seen from the back of an empty movie theater. The screen, scintillating bright, absorbed all feeling and sound. It turns out this screen had nothing on it, yet everything on it. The photographer, Hiroshi Sugimoto, made the image by taking a long exposure of a movie playing on the screen. He made a series of these over 4 decades, starting with a crumbling theater in the East Village. When Sugimoto developed the film, he noticed that sad movies produced a final screen with a darker glow than happy movies.

I snuck into the reading room one night, concealing my tripod and Leica M10 Monochrom camera in a knapsack. I closed the door behind me. I was alone in the dark, surrounded by eight image screens. They were black and displayed no patients, having been powered down for the evening. I set up my camera on its tripod, and positioned it in front of one of the monitors. My camera’s distinguishing feature was that it could only see in black and white, like me by that point. I powered on one of the computers, and felt my heart pound as I opened one of my old chest CT scans - one that found near-fatal blood clots. I opened the shutter of my camera and scrolled through the hundreds of images in my scan. I felt myself fragment into millions of grey pixels of sand, then let the sea of images wash over me, then waterboard me, as I viewed my broken body. When the torture was over, I closed the camera shutter, and my eyes.

reflection forum